Just shy of half a century is how long its been since director Shinya Tsukamoto entered filmmaking. He’s become one of the most celebrated filmmakers of this generation next to the likes of Takashi Miike and Sono Sion, and for good reason, aptly applying his visionary and stylish craft to numbers like his 1998 film, Bullet Ballet.

Granted, Tsukamoto’s accolades didn’t come without some requisite pot-stirring along the way, which is exactly what Bullet Ballet achieved at the time, becoming one of the most polarizing pieces of work. Some critics have taken a liking to his “aggro art” style more so than others in the years since surfacing on the cinema map. The film certainly even goes out of its way breaking all sorts of rules during the more raucousing moments of action and danger, culminating its psychedelic, trippy, edgy indie feel to go hand-in-hand with its 35mm black-and-white lensing.

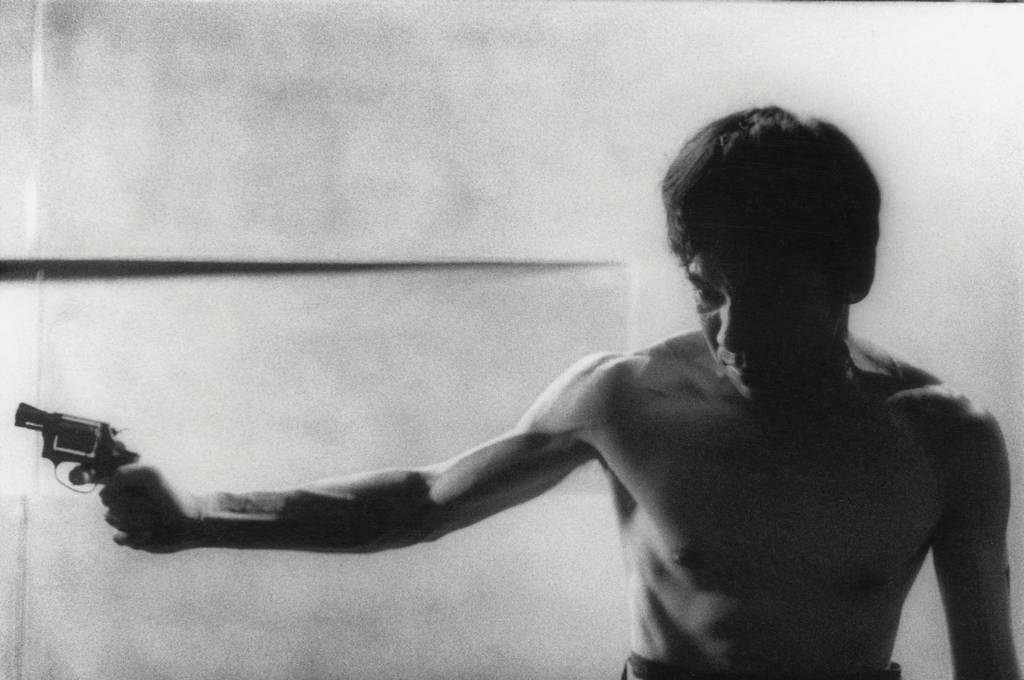

All, in the end, to craft a story about a successful TV advertiser and his joruney into a self-depricating hell of inner-turmoil when his live-in girlfriend allegedly kills herself, compelling his sudden obsession with guns, the yakuza criminal underworld, and a gangster’s suicidal woman. Tsukamoto himself stars here as our tormented lead character, Goa, who fully immerses himself into the downward-spiraling madness that unfolds. His intial struggle to find a gun or anyone who might sell one to him begins after he’s assaulted by Goto and his gang one evening after confronting Chisato for biting him on one occasion.

Goa’s need for vengeance is precisely the exposition that further transcends Bullet Ballet into an even darker form of itself before diving into its more redeeming beast. Kirina Mano plays Chisato, whose penchant for teasing death despite other aspects of her toxic behavior are part and parcel to Goa’s fascination with her. Takahiro Murase’s Goto is the quintessential man’s man tough guy and acting lieutenant of his gang for boss Iei, played by Tatsuya Nakamura.

Both Chisato and Goto have their layers peeled back one by one over a period of time in the second half following a pivotal moment where Goto’s desire to use Goa’s gun leads him to make a huge mistake. That mishap ultimately corners Goto and his gang as marked targets by a hitman who now wants Goto, Iei and everyone dead – that is, unless Goa has anything to say on it.

After all said and done though, it’s all about the gun – nothing short of symbolic as more than a tool some individuals see it as. Tsukamoto’s vivid and profound imagery in illustrating the violent evolution that spawns from man’s cyclic need to feel powerful at the hands of something dangerous and mortally deadly may seem exacerbating to some, but I think it’s purely elemental and poetic to Tsukamoto’s narrative.

This is the sort of thing he exhibits in his newest film, Killing, only the MacGuffin is a sword. In this instance as you look into Tsukamoto’s patterns for storytelling, you sort of get the idea that a sword is no different from a gun. Tsukamoto’s inherent focus on humanity’s naivete when driven to burn the proverbial candle on both ends is what’s important.

The reception of his mechanics by which he uses to execute these stories is entirely up to the viewer. Regaedless though, twenty one years later – and though it may just be the fan in me in my newcome discovery of Tsukamoto’s life’s work – I’m not complaining. Bullet Ballet goes as hard and dissonant as an introspective and rippling tale such as this one should be, and I’m more than pleased that it’s what’s helped make Tsukamoto the acclaimed auteur he is today.