Tackling award-winning literature for a change of pace, it was Fuminori Nakamura’s 2002 Shincho-prized novel, The Gun, which ultimately sought the interest of director Masaharu Take for his subsequent endeavor at the time. Doused in hypnotic black and white, the celebrated In The Hero and 100 Yen Love helmer’s adaptation enjoins a cast here led by Destruction Babies co-star Nijiro Murakami for an intriguing, introspective view into the downward spiral of a man numb to his own decaying state.

Opening with a shot of our lead character, Toru (Murakami), he discovers a gun at a murder scene and takes it into his possession. It’s the start of a dual lifestyle for the young college student whose campus days sees him often with girl-crazy friend, Keisuke (Amane Okayama) whose only main concern is to get laid and party as frequently as possible – something entirely opposite of Toru’s own mindset most days. Their double date with two girls one evening lands him in bed with a female he conveniently saves in his phone as “toast woman” (Kyoko Hinami).

Separately, Toru’s burgeoning relationship with a chipper fellow classmate named Yoko (Alice Hirose) proves to be something of a rollercoaster as well. It’s a slow start, initially, but then gradually takes a life of its own to a point where things may feel prospective. In the course of all these developments, however, is the gun he keeps at home, and his brimming curiosity about using it whether he did so on something, or someone. His troubled childhood also factors in with moments on which he reflects on his own mother and father – the latter who now lays dying in a hospital.

Between this, Yoko and “toast woman”, his only unyielding thought – a daily constant – is the gun. Finally compelled to carry it on him one evening, despite the illegality and potential consequences, as well as the full knowledge of the gun’s origins. A grim incident one evening precedes the morning a detective (Lily Franky, Hirokazu Koreeda’s Palme d’Or-winning Shoplifters) running high on his instincts as he tracks down Toru, effectively cornering him as a key suspect.

Take’s The Gun is less so a murder mystery, and more involved as a brooding character study that elucidates the kind of personality that takes shape for someone like Toru. He’s young, handsome and for all intents and purposes, comes acrosss as the most seemingly-innocuous kind of individual anyone may come across. He’s Light Yagami without the savior complex and perfect home setting, though just as mentally fucked up in a sense.

His temperament is usually impulsive around others on certain level. On top of being a womanizer, he’s terse, aloof and he’s always smoking. His body language tends to be slightly brash and fidgety, and we especially see this at one point in the film when he starts a chit chat with a patrol officer at night while sitting in the park regarding possible crime activity in the neighborhood.

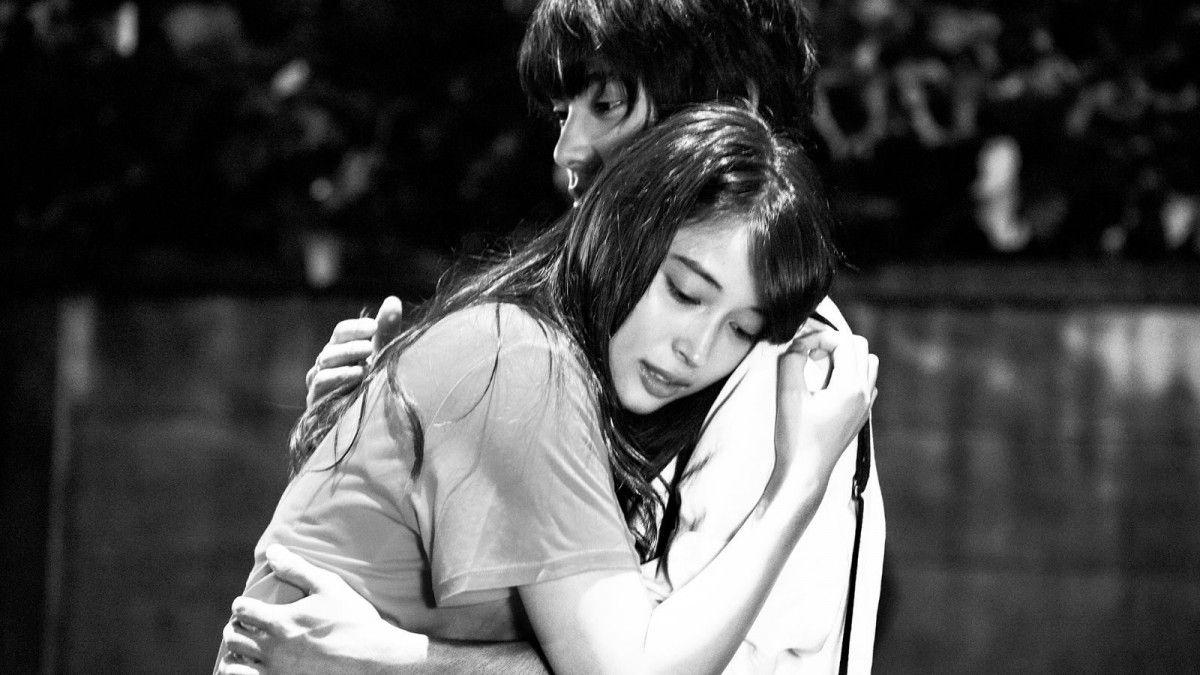

He’s coldest with the people closest to him, especially Yoko, a trait that gradually takes a back seat one peaceful evening when she calls him to have company. Theirs is a friendly walk from campus to her dorm preceding a moment when she hugs him; it’s that kind of vulnerability Toru isn’t used to as he’s visibly dumbstruck when it happens. That instant, while emotive and droll, bodes as a short-lived as long as Toru’s concomitant addiction remains.

Franky’s detective character sends things off to the races in one of the best and most thrilling moments in The Gun – the war of wits between himself and Toru as our lead character struggles to maintain his composure despite the detective seeing almost right through him.

It’s important to note, though, that The Gun tackles something far more internalized. The film is much ado about Toru’s lack of intimacy and his use of sex as a coping mechanism – numbing him to his own looming deviancy, emboldened in part by having the gun, and the idea planted in his mind about what it makes him. Things eventually unhinge in the third act and though it leads to a question of whether or not Toru will be able to catch himself before it’s too late, the remaining moments in the third act aren’t entirely solid.

The film could have ended a few minutes earlier following a scene between Toru and Yoko. Instead, it hits something of a cliffhanger, and it’s important that you watch the film all the way through to catch on to the imagery to know if what you’re seeing is real. The ending’s lurid transformation to color is the pièce de résistance, drawing an earth-shaking conclusion to Take’s The Gun, culminating a compelling, often mesmerising allegory on mental illness, abandonment and loneliness.