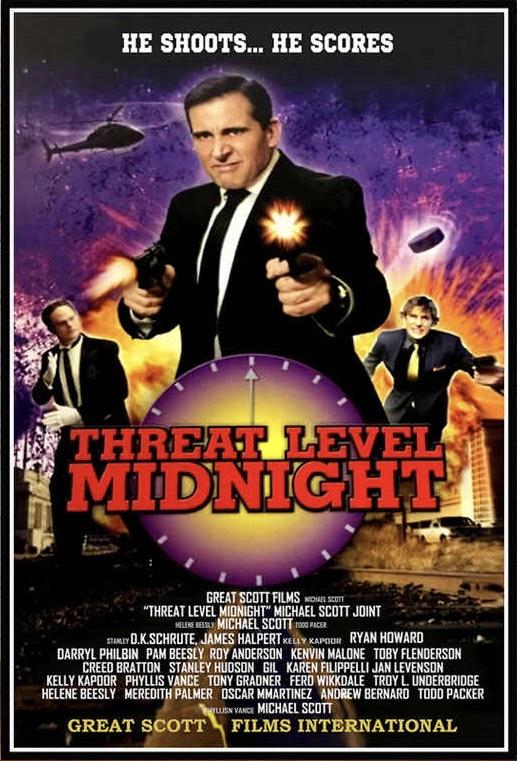

This year marks the tenth anniversary of Steve Carrell’s exit from the wildly popular (and perpetually streamed) sitcom, The Office. After seven seasons of good natured mayhem, Michael Scott was preparing to leave the Scranton, PA branch of Dunder Mifflin forever, but not before one final loose end was to be tied up; the premiere of his indie action masterpiece, “Threat Level Midnight”.

First revealed as a B-plot in season two when the employees stumbled upon (and did an impromptu table read of) its script, TLM would continue to be mentioned and teased throughout the following seasons. At the request of Carrell himself, “Threat Level Midnight” was made a reality for the whole world to see.

This is the story of super-agent Michael Scarn (Michael Scott), a man with a history of saving the All-Star games of various sports leagues from the evil Goldenface (Jim Halpert). But everything falls apart when he fails to stop a bombing at the WNBA All-Star game. Scarn’s basketball playing wife, Catherine Zeta-Scarn, is killed in the blast and Michael leaves the secret agent game behind. But when Goldenface resurfaces to bomb the NHL All-Star game, Scarn and his faithful (robot?) butler Samuel (Dwight Schrute) have to stop the terrorist once and for all.

Shot over several years and featuring almost every major (and some minor) character from the previous 6 seasons of the show, “Threat Level Midnight” feels like Michael’s magnum opus. While clearly made for laughs, TLM proved to be a surprisingly sincere look at amateur filmmaking and what happens when a new artist’s ambitions far outstrip his abilities and resources. For this reason, TLM is a terrific example of indie filmmaking that shows surprising nuance.

Many of you are rolling your eyes after reading those last few paragraphs, but please take a break from said eye rolls (seriously, it will give you a splitting headache after awhile) and go on a journey of discovery with me…

Deep Cut Homage

There’s never been any doubt that Michael Scott is a cinephile. We see how movies influence his worldview as well as his (strange) behavior throughout the series. But Threat Level Midnight’s opening scene shows he’s far more observant than we may have given him credit for.

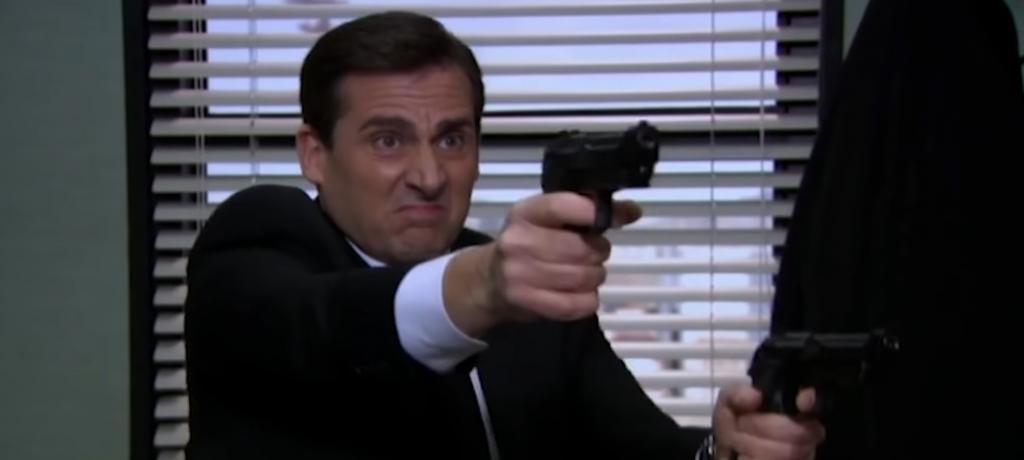

There is nothing more John Woo than a man emptying two pistols worth of bullets into an enemy. In a Woo film, the double tap is frowned upon; anything less than 32 rounds to the chest just won’t cut it. This is exactly how Michael Scarn responds to an assassination attempt by Bob Vance’s mailman hitman character. A surface level homage would have stopped there, but Michael goes a few levels deeper with the sound design; specifically, ANIMAL SOUNDS.

With all of Woo’s trademark ballistics, it’s easy to overlook his amazing sound design which often includes the use of animal sounds to help sell the emotions of an action scene. The clearest example of this is the final fight from Broken Arrow. For all of its Americanization, Broken Arrow still possesses many of Woo’s eccentricities, including the sounds of actual Tigers while Christian Slater and John Travolta are duking it out over a nuke. It’s surprisingly subtle, almost subluminal, but was a deliberate creative choice that few other directors would have made.

What animal(s) does Michael Scott choose to accompany him drawing dual pistols from behind his desk? An Elephant and a Lion of course… Like much of Threat Level Midnight, Michael Scott manages to turn a good idea into something tone deaf and ridiculous with absolutely zero subtlety. He gets points for a truly deep cut, but immediately loses them for making a terrible creative choice (and the actual “stunts” are hilariously bad). In a way, this sets the stage for what is to come: a newbie filmmaker constantly stumbling over his own inexperience and lack of self awareness.

Effectively Disguising a Location

Half the fun of watching Threat Level Midnight is seeing how Michael turns places we’ve seen a hundred times into different locations for his overly ambitious film. In many cases, he makes use of clever (if not incredibly obvious) tactics that ALMOST pull it off.

We know Michael lives in a bland condo, but for the purposes of this film it needs to look befitting of the name Scarn Manor. How he does this is actually somewhat (but not entirely) effective. The scene opens with a stock image of a giant mansion and/or palace before cutting to Michael’s bedroom now conspicuously adorned with candles. On its own, this looks ridiculous but it’s his use of a warm filter that helps tie the stock image to the crappy condo. Yes, the candles are a poor man’s attempt at making the interior look fancy. No, it doesn’t sell us the illusion. However, had we not been so familiar with Michael’s condo (or any of the other locations) we might be ALMOST inclined to buy into it.

The same goes for The White House, but this one is actually even more clever (though no more convincing). Another stock image introduces us the the location (and gives us the EXACT address, zip code and all) before we cut to the dimly lit conference room meant to serve as the oval office. The low lighting helps to somewhat mask the fact that this is just a conference room with the shot composition and production design doing some much needed heavy lifting. Shots are carefully selected to hide the visual trickery happening; something that falls upart in the hastily shot later scenes as the less careful camera angles expose the seams of Michael’s illusion.

Fun with Production Value

Seeing as how this was filmed over the course of several years, there are WILD swings in production value as well as production design. The first noticeable shift is when Michael seeks the tutelage of the “totally not racist” Cherokee Jack, played by Creed. They clearly had the money to rent out an ice skating rink for extended periods and took full advantage, creating a surprisingly effective training montage with flowing shots and only marginal stupidity (mop the ice?).

The same goes for the following speed skating / gunfight-on-ice scene with Goldenface. Yes, Michael still awkwardly dodges bullets but the flowing camerawork and editing actually create a sense of energy that is sorely lacking from every other action scene.

Later in the film, we somehow switch genres from a spy story to a detective noir when Scarn visits the Funky Cat night club. Suddenly, the lighting and cinematography start to look like a real movie even if it feels out of place in the story both stylistically and narratively (more on that later). This boost in production value / design makes the transition back to earlier footage that much more jarring. Sometimes consistency trumps production value…

Do the Scarn

This scene is perfect and anyone who feels otherwise has no joy in their lives. Also, Angela has to say “sex choochoo”, so there’s that…

Guerilla Filmmaking 101

During the film’s first (and only?) screening, Michael reveals that they crashed a youth hockey game to shoot the film’s climax and almost got the home team disqualified. In fact, we actually SEE the moment where he gets ejected from the game. But for a brief 10 or 15 seconds, he manages to give the film a small sense of scope that it desperately needs.

The filmmakers wisely pivot, coming back on a different day (i.e. renting the skating rink again) to try to fill in the gaps of the finale. We learn that “not at all problematic” Cherokee Jack has died; filling Scarn with the resolve he needs to save the All-Star game… and they ALMOST pulled it off.

There’s a trick to this kind of illusion. Filming guerrilla-style to get great wide shots is a good idea, but when you come back to do more controlled mediums and close-ups, it’s vital to have a handful of background actors to help maintain the illusion and tie in consistently with the wide group shots. Michael Scarn is magically transported to a noticeably empty skating rink where he shoots the puck into space and saves the day. Oops.

Continuity is Your Friend

Another major byproduct of protracted film production is the need for someone maintaining continuity. Nowhere is this more evident than the final scene where Scarn takes on a new mission from the President (Darryl Philbin)… The same President who set up the bombing of the NHL All-Star game in the first place to collect the insurance money. Based on the shoddiness of the betrayal scene, it’s obvious that this was shot much later to help setup the final act of the film. Not a terrible idea, but one that had story repercussions that Michael hadn’t considered or accounted for.

Another continuity detour happens when the film abruptly switches genres and becomes a detective noir. The Funky Cat sequences are some of the most cinematically competent in the entire film and stick out like a sore thumb. Sure the lighting, cinematography and production design are all top-notch (comparatively), but it feels like it was spliced in from a different movie entirely. It’s hard to fault an artist wanting to flesh out their story while showing off new skills, but it just makes everything around it look that much worse; best to save that for the next one.

Michael Scott and ‘Save the Cat’

An area where “Threat Level Midnight” is unquestionably strong is in its pacing. The film might be a trainwreck, but it’s never a boring trainwreck. Coming in just shy of 25 minutes, the film has an average scene length of about 90 seconds. If you stretch the runtime out to feature length, you get the equivalent of 5 and a half minutes per scene. That’s actually a good place to be. Scenes never drag on too long (unlike so many indie films) and there’s always a new story development being revealed.

The film also has rock solid structure. It’s obvious that at some point, Michael Scott stumbled upon Blake Snyder’s ‘Save the Cat'(2005) and took its lessons to heart. There’s even a part where Scarn announces he’s hit his lowest point; the only way he could be more obvious is if he’d ordered a drink called “dark night of the soul”. Like most aspects of this film, a lot of Save the Cat’s lessons are applied with a considerable degree of incompetence. From the “kill the cat” moment of blowing up Toby’s head (from 5 different angles) to the midpoint climax involving Goldenface shooting Michael Scarn in the “brain, lungs, heart, back and balls”, the story beats often seem forced or extremely on the nose. We’re lead to believe that Scarn either bounced back from his bullet wounds in a day or the film just took place over an entire year; either way, WTF?!? Fortunately, before you can finish your “wtf” thought the film has already moved on to the next story beat. THAT is good pacing.

In Conclusion

After re-watching Threat Level Midnight, it’s hard not to recall some of my own early films. Seeing the days when my reach far exceeded my artistic grasp and acknowledging that those rough early days were a valuable part of my growth as a filmmaker. What my work lacked in competence, it made up for with enthusiasm and energy; something that makes them endearing to me all these years later (despite the fact that they are objectively embarrassing).

Any indie filmmaker worth their salt can see a little bit of their own early work in TLM, which is a testament to those who created it. “We made a movie!” episodes are a long and often entertaining tradition in the world of sitcoms, but there is an honesty to Threat Level Midnight that makes it resonate with indie action filmmakers. In a way, we’ve never felt more seen (or insulted).

Watch Threat Level Midnight below, and remember to visit NBC.com for more on The Office.