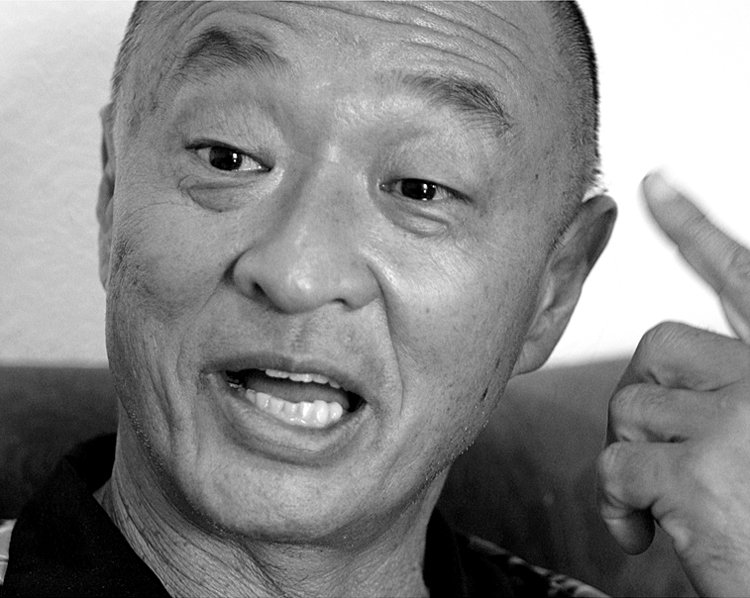

I found out this morning, the same way most of us did: a quiet post on social media, then a flood of broken-heart emojis under that iconic Mortal Kombat poster. Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa is gone. 75 years old. A stroke. And just like that, the man who could silence a room with a single slow tilt of his head is no longer with us.

If you grew up in the ’90s renting VHS tapes until the magnetic ribbon wore thin, you already know the moment. Mortal Kombat, 1995. The banquet hall. Shang Tsung, in that black-and-gold robe, leaning back in his throne like evil itself had decided to take a coffee break and enjoy the show. “Your soul is mine.” Four words, delivered with this velvet menace that made every 12-year-old in the room simultaneously terrified and obsessed. That was Cary. He didn’t just play the villain; he made villainy look like the most natural thing in the world.

But here’s the thing the highlight reels sometimes miss: he almost never played the same villain twice.

Picture this: In the film, Dolph Lundgren and Brandon Lee are the buddy-cop leads, but the second Tagawa steps on screen as Yoshida—the yakuza boss with the long black hair, the silk suits, and that samurai sword he uses like an extension of his own body—the movie suddenly belongs to him. He beheads a guy on a pool table, smirks while his henchmen torch a nightclub, and delivers lines like “I’m gonna finish you off… with my hands” with this calm, almost bored certainty that makes you believe he absolutely will. It’s pure ’90s excess, and Tagawa is the wicked heartbeat of it. Showdown in Little Tokyo was the first time a lot of us saw what he could do when somebody finally let him go full throttle.

There was the icy, coiled-spring danger of Satoshi Takeda in Revenge, a sensei who could gut you with a katana or just a disappointed sigh. There was the haunted dignity of Nobusuke Tagomi in The Man in the High Castle, a man carrying the weight of two timelines on his shoulders and somehow still finding room for kindness. There was the quiet, almost tragic authority of Admiral Yamamoto in Pearl Harbor, a performance that dared you to hate the historical figure and then gently asked you to understand him anyway.

Cary Tagawa never had the A-list leading-man run that his talent deserved, something he talked about openly, the limited roles for Asian actors, the perpetual “exotic heavy” box Hollywood kept trying to put him in. But watch any of his performances and tell me the screen didn’t belong to him the second he walked into frame. He had that rare, old-school presence: the kind where the camera loved him even when the script didn’t quite know what to do with him.

Tagawa was the son of a Japanese stage actress, Mariko Hata (also known as Ayako), and a Japanese-American father who served in the U.S. Army. His parents named him after actor Cary Grant and his brother after Gregory Peck. Raised as an “Army brat,” he lived in various U.S. cities, including Fort Bragg, North Carolina; Fort Polk, Louisiana; and Fort Hood, Texas, before the family settled in Southern California. He attended Duarte High School, where he began acting, and later studied traditional Japanese karate at the University of Southern California. Tagawa returned to Japan to train with the Japan Karate Association and developed his own martial art form, Chun-Shin, which he taught throughout his life.

Tonight I’m doing what a lot of us are probably doing: firing up the timeless Mortal Kombat movie, turning the volume way up for that banquet scene, then queuing up The Man in the High Castle because I need to hear Tagomi speak softly about hope one more time. Somewhere in the middle of all that, I’ll probably cry like the overgrown fanboy I am.

Rest easy, Sensei. The arena feels a lot smaller without you.

Your soul was never anyone’s to take. Thank you for letting us watch you carry it anyway.

Picture courtesy:

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Cary-Hiroyuki_Tagawa.jpg