IN HER BOOK, Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome, Dr. Joy Degruy examines the myriad ways that African Americans’ history have been fragmented by a racist society, how generations of disenfranchisement, abuse, and racist socialization have robbed black people of the underpinnings of culture and filial structure, and how as a people they’ve been affected at the cellular level by the Transatlantic slave trade, the Jim Crow era racism that followed, and the buttress of systemic racism that still thrives at every level of the national infrastructure to this day. “Although slavery has long been a part of human history,’ she writes, ‘American chattel slavery represents a case of human trauma not comparable in scope, duration, and consequence with any other incidence of human enslavement.” She argues that African Americans are “slavery’s children”, are thus afflicted with survivor’s syndrome, and she defines Post Traumatic Slave Syndrome (PTSS) as “a condition that exists when a population has experienced multigenerational trauma resulting from centuries of slavery and continues to experience oppression and institutionalized racism today.”

While watching Queen & Slim (hereafter, Q&S), I got a sense of this awareness being present in Lena Waithe’s script. It’s notable that the film was also directed by a woman, Melina Matsoukas, making this a trinity of women of color seeking to tackle the subject of the black diaspora, and fighting through the vehicles of cinema and literature to in some way heal the wounds of the past and present. A tall order. The narrative of Q&S takes a sober look at American life through the multi-shaded lense of blackness, offering dramatic commentary on the many intertwining conversations on what it means, blackness, precisely. There is the dramatized notion of vacant esteem and its consequences for the black community, touched on subtly in some decidedly frustrating characterizations present in the film (you’ll know them when you see them), and expounded on at length in Degruy’s book -which is definitely worth reading.

It made me angry to watch Q&S, but it’s an anger inexorable to my experience as a black man in America. Look, I had a friend, a Latin American, who despite how close we were, or, rather, how close I thought we were, could never quite connect with or understand the foundation of that anger. Instead he judged me arbitrarily over it. He had some concept, tangentially, of racism in this country but there was no true solidarity in said understanding. We often crossed swords on the matter in fact, my concerns being dismissed as “negativity”. I had another friend, a white police officer, who, it bears mentioning, I was friends with long before he became a cop, that I’ve had some heated arguments with over the subjects of police brutality, racial profiling, and the disingenuous and, frankly, dishonest statistical crime rate reports that cast black people as uniquely criminalistic. A redoubtable non-racist white man, I watched him over the years transform into an unwitting custodian to some of the harmful and incorrect stereotypes that keep black people in perennial danger in the US environment on the basis of their skin color alone. The more melanin, the greater their exigency.

This is important because the narrative of this picture suggests a pointed acquiesce to the notion that race in America, as a subject, is at best a complicated one. And the more that we as a society attempt to undermine any examination of its weight in discussion and policy, the more refined becomes the ever-present powder keg of racial dissonance, one that, when it explodes, will not discriminate in its choice of victims in the blowback.

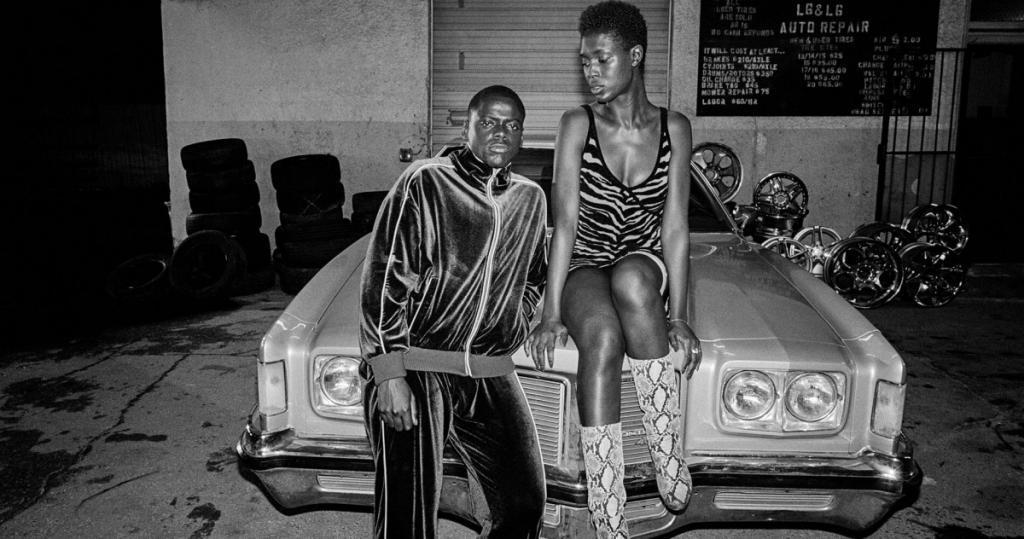

I like to think of Q&S as a romantic crime drama with a consciousness. This is far more fitting -and, frankly, less uncomfortable- than thinking of it (the film, the story of its titular characters, their legacy, so to speak) in terms of Bonnie & Clyde as an analog. For starters, the problem with the latter idea, besides it being grossly simplistic, is the slippery false equivalency of it. Bonnie & Clyde were willing criminals, murderers who, along with at least six police officers, killed four civilians during their crusade of robbing mostly mom & pop businesses and gas stations during the era of the Great Depression. They were in no sense heroic, despite the mythology built up around them for flaunting their nihilistic indifference for the law and robbing a few banks along the way to exploiting the hardships of people who were already weathering destitution. Queen (Jodie Turner-Smith) and Slim (Daniel Kaluuya), on the other hand, were just two lonely dark skinned black people on a Tinder date who had the misfortune of crossing the path of a racist white cop. Remove the adjectives “dark skinned”, “black”, and “white” from the previous sentence and, because the scenario is so common, you’ll get a sense of the same words filling the same spaces in their absence. A point emerges!

One of my favorite things about Waithe’s script, and Matsoukas’ direction of it, happens during the hardest scene to watch; the fateful confrontation with the cop. It’s a messy scene, one loaded with triggering nuance for any viewer of color. I should qualify it; any black viewer… The cop’s barely hidden enmity, Slim’s futile efforts to show respect in the face of it, and Queen’s all too familiar offense to the abuse of power, it’s the Gordian knot of race relations, power dynamics, and the incendiary potpourri of them taken together. I think it’s interesting that Queen is a lawyer, and I think that she is in a sense an audience surrogate. I think it’s also interesting that when Slim is introduced before the opening credits, we learn about his awareness to the importance of community and how he values buying “black owned”. There are arguments being proffered through the expression of these characters, and plenty of subtext. Such as on America’s devaluation of its citizens over material and industry, and how the American dream is exactly that; a fantasy given sparkle in the collective unconscious, our waking lives scattered below as the flotsam of its fallacy. This representation is offered by Bokeem Woodbine, playing Queen’s uncle Earl, a war hero who becomes a hustling pimp as a civilian, seen buckling under the weight of his insecurities despite the pomp and circumstance of maintaining an air of alpha masculinity. The crack in the vase is also shown through Queen herself, who though an educated attorney is portrayed as broken inside by her own deep seeded anger, not to mention a distinct lack of interpersonal relationships at the time she meets Slim.

The tragedy is in watching Queen heal some as she gets closer to Slim over the course of the film, echoing an argument from Degruy’s book on the importance of love. We watch Slim, who is presented at first as tentative, heal as well through his relationship with Queen and through her gain poise and conviction. But alas the process of healing sometimes is as messy as the injury. I cried inside over the expression of this idea cinematically. Consider an intimate sequence intercut with the violent development of a riot, consider also a road sequence shot through a picturesque countryside that palliate the optics but is set to sad music.

Speaking of music, there’s a lot of it in this movie. Enough of which that the soundtrack presents itself as another character full of bombast and the celebration of soulful black artistic expression. Queen and Slim are insulated along their journey in this oasis of black love, and also protection from the black communities they pass through, for the most part, that identify them as archetypical in their push towards survival upstream and against the odds of judgement tinted blue. That confrontation with the racist cop, it keeps getting described in the media as a “routine traffic stop”. But even without video, any black body knows there was nothing routine about it. So too is there nothing routine about this road trip.

So no, Queen & Slim are no Bonnie and Clyde. There’s much more to them than that. And to echo something Queen says at one point early in the film, it’s not about vanity but about the evidence of value.

QUEEN & SLIM is now available on Blu-Ray, DVD and Digital from Universal Pictures Home Entertainment