The Long Road

Starting as early as the mid-80’s, the Hong Kong film industry was making some inroads into Hollywood. Maybe it was the insane amount of money being casually tossed around… or maybe it was the giant communist nation that was set to retake control of it within the next ten years; whatever the reason, the biggest action film producer in Asia was looking to branch out. Seasonal Films led the charge with crossover B-movies like No Retreat No Surrender (1986), American Shaolin (1991) and Superfights (1995). The films possessed a so-bad-its-good quality that make them great fodder today but didn’t make enough of a splash in their day to move the needle.

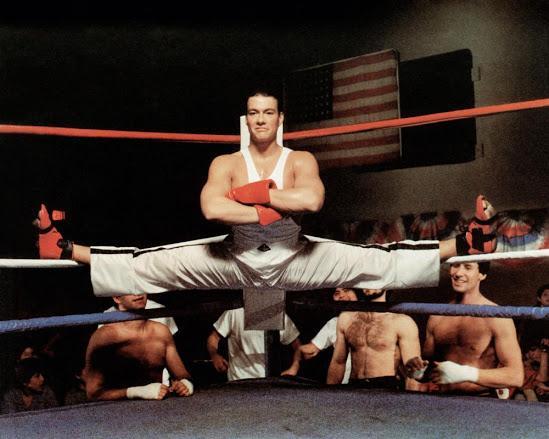

| America just wasn’t ready for this much awesome |

Even the mighty Jackie Chan, already an international star, fell on his face when he tried to break into Hollywood with The Protector (1985). The film bombed so hard and was such a lousy experience for him that it inspired Chan to turn his back on the U.S. and double down on his native Hong Kong starting with the self-produced Police Story. This newfound vigor would help him become a bigger star than ever, though it was obvious that he never took his sights off Hollywood.

The first real victory wouldn’t come until 1993, when director John Woo was able to leverage the strength of films like The Killer, Hard Boiled and A Better Tomorrow to make a major play for Hollywood. Up to this point, Woo was still unknown to anyone without access to a Chinatown video store and a sense of adventure; luckily for him, one of those people in the know was action star Jean Claude Van Damme.

Before coming to LA to become an actor (“actor”), Van Damme tried his luck in the Hong Kong film industry… and failed miserably. Though Hong Kong was indifferent to him, it never actually fell off his radar. Now, armed with a shiny new 5 picture deal with Universal, he sought out Woo’s talent in dramatic action filmmaking to help kick his career into high gear.

| This is what “high-gear” looks like, kids! |

The end result, Hard Target (1993), felt like Woo through a filter. It lacked the kind of dramatic punch and ultraviolence we all retroactively love about his films and is replaced with Van Damme mugging for the camera and throwing slow motion kicks. The blame has been thrown squarely at the feet of the studio as well as the film’s star. Woo was often treated like cheap labor by those above him and often butted heads with the studio over most aspects of the production until he was unceremoniously kicked out of the editing room. Woo wasn’t used to being on such a short leash or having such “limited” production schedules. Unfortunately, this would become a common trend that would affect practically EVERY Asian filmmaker who attempted to make the jump…

…Which brings us to 1996. Despite their best efforts to remain ignorant to it, Hollywood was finally starting to acknowledge the talent coming out of Hong Kong both in front and behind the camera. Hard Target, despite its turbulent production, ended up being a hit. Two years later, the HK-style choreography of Mortal Kombat (courtesy of star Robin Shou) helped that movie make its studio a tidy profit. The time seemed right… to exploit this new well of talent for financial gain.

Fun Fact: the Hong Kong government has a relationship with its film industry that can best be described as Combative. Getting filming permits was often impossible and cooperation was nonexistent. Actually getting films made in the city often required guerrilla filmmaking techniques such as stealing shots and running when the cops showed up. This lead to many HK filmmakers seeking other, more film-friendly places to work. Bruce Lee did it with Way of the Dragon (Italy), and now Jackie Chan was doing it with films such as Wheel on Meals (Spain), Thunderbolt (Japan), and Rumble in the Bronx (Vancouver!).

Despite its hilariously inaccurate portrayal of New York gangs and a location that couldn’t be more Canadian unless all the street signs were in French, Rumble In The Bronx was seen as having serious potential appeal for American audiences. New Line Cinema released the film in February, a notoriously slow month following the “dead zone” of January, a time when studios release the films they have little to no faith in to die miserable deaths (Who remembers Antitrust? With Ryan Phillippe? Didn’t think so). With little in the way of competition, Rumble was able to stand out with its attention grabbing stunts and mindblowing fight scenes. Most Americans had never seen anything like what Chan was serving up to them and the film went on to be a box office hit. It wouldn’t be long before hardcore fans began whispering about the superior, uncut Hong Kong version of the film; something that would become a badge of honor for die hard HK film fans in the years to come. Long story short, Americans were hooked.

| Sadly, the film’s popularity wasn’t enough to save the ailing hovercraft. |

After the huge success of Chan’s breakthrough in the west, studios started buying up the rights to his entire filmography. Before the end of the year, Jackie would grace theaters again with Supercop (Police Story 3). Released in November, this film had a bit more competition than Rumble did and only managed to gross half as much (though we were still treated to the same degree of invasive editing this time around). We were also introduced to Michelle Yeoh, often referred to as “the female Jackie Chan” in articles and print advertising at the time.

Moreso than John Woo, Jackie had opened the door to not only himself but other HK actors as well. Rumble In The Bronx was a true game changer; a film that showed us what action films COULD and SHOULD be. Pandora’s Box had been opened, and the action movie landscape would never be the same.

Despite its troubled production, and with three years and 4 films of hindsight, Hard Target would become known as one of JCVD’s more highly regarded films. Van Damme ended his five picture deal with Universal by somehow stumbling across the opportunity to make his directorial debut with The Quest, a blatant ripoff of Bloodsport with a bigger budget but considerably less fun. After a messy production and lackluster theatrical run, he moved on to a new 3-picture deal with Sony Pictures. As some sort of strange ritual, he started his tenure at this studio the same way he’d started at the previous one; by working with a talented Hong Kong director looking to break into Hollywood before Communist China took back Hong Kong.

| Maybe this whole “Red Scare” thing has been blown out of proportion. Let’s all put our guns down and take a few steps back… |

In this case, the filmmaker was Ringo Lam, and the film was Maximum Risk. Seeming to have learned his lesson from his (poor) treatment of Woo, Van Damme (and the production company) seemed to give Lam more respect and creative control than his compatriot received three years prior. The film has a stylish brutality to it that is signature Lam and Van Damme gave a quality of performance that few thought he was capable of. Lam’s style of filmmaking and action seemed to mesh well with the studio and star he was working with and the results were better than they had any right to be. Unfortunately, Van Damme’s star had faded considerably in the U.S. and the film underperformed at the domestic box office; fortunately, its international revenue helped it to become a success.

Sadly, despite its quality, Maximum Risk failed to jump-start Lam’s film career in the West or save Van Damme’s career from its downward spiral; though the two would work together several more times in the future.

Play it again Woo….

After butting heads with Universal over Hard Target, John Woo decided he needed a change of pace and proceeded to butt heads with 20th Century Fox over a new movie: Broken Arrow. If Hard Target was a Hong Kong film run through a Hollywood filter, Broken Arrow was a HK movie diluted in Hollywood convention. Woo seemed determined to prove he could make an American-style action movie, complete with the most American of action tropes: exploding helicopters (at least 3).

One of Woo’s greatest strengths in Hong Kong was born almost purely out of necessity; his ability to make almost any action setup spectacular. While his American counterparts were dropping millions to have helicopters whiz between buildings and blow the roof off a skyscraper, Woo had to turn relatively mundane action setups such as a shootout in a hallway into an epic orchestra of violence. He was a master at executing amazing action sequences regardless of his limited resources. In trying to emulate big-budget Hollywood, Woo all but abandoned his greatest strengths as an action filmmaker.

That’s not to say the film doesn’t have a few Woo flourishes. In addition to the expected visual symbolism (butterflies on the water), and the hero/villain dynamic (old friends who end up on opposite sides of a conflict), the final fight between stars Christian Slater and John Travolta is accompanied by TIGER SOUNDS! Woo claimed he was watching a lot of American television after finishing Hard Target in an effort to understand western audiences better. It may be for that reason that the film feels like a made-for-television movie with a huge budget.

| Pictured: The most John Woo moment of Broken Arrow |

The U.S. wasn’t the only place that Hong Kong talent was defecting to in the 90s. Hollywood’s favorite cost-saving backlot was also benefiting from the imported talent; in many cases, the SAME imported talent.

Once A Thief is a lesser-known John Woo film compared to his modern classics, but some Canadian producers thought it had breakthrough potential and commissioned Woo to remake it as the backdooriest of backdoor pilots. Strangely, despite the fact that Woo directed the film himself, it feels like a copycat aping his style. Even compared to his compromised Hollywood work, Once A Thief barely has anything resembling Woo’s flourish… or any flourish at all. With this remake, Woo managed to create the most aggressively average film of his career; the subsequent TV series would only survive for a single season before being put down.

| Pictured: The closest thing to a John Woo moment in Once A Thief… |

| In a year’s time, one of these men would be made famous by a combination of Paul Thomas Anderson and a prosthetic dong. |

For all its missteps and blunders Studios made in trying to reign in the talent it was also trying to cultivate, the fact that American audiences were given the opportunity to experience such great work in an actual theater counts for something. 1996 would turn out to be ground zero for Hong Kong’s invasion of Hollywood. The next five years would prove to be very exciting.