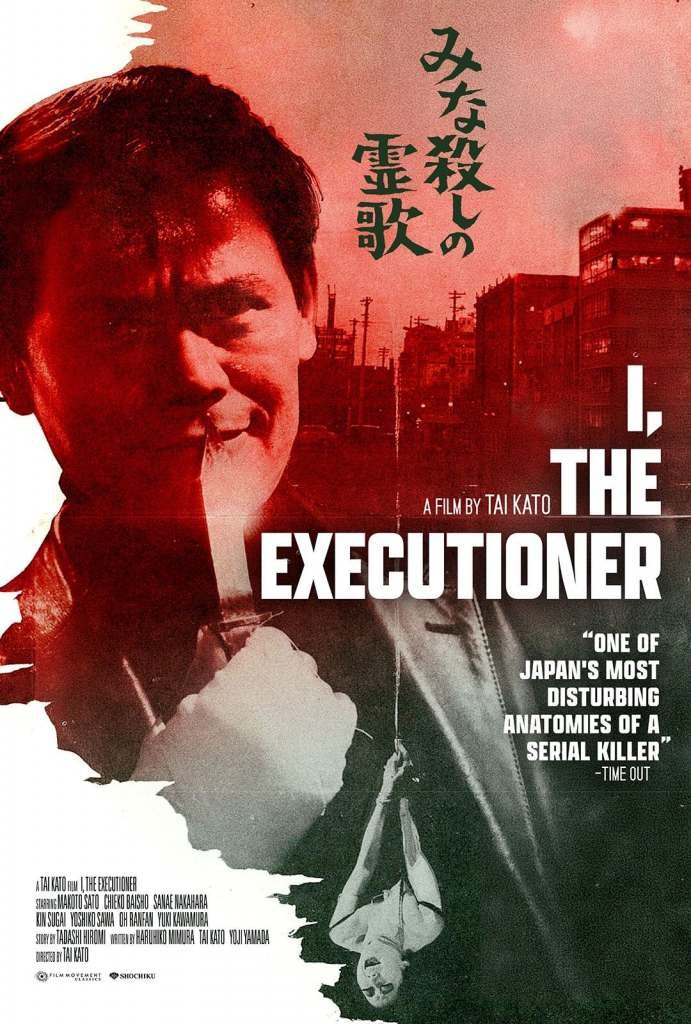

I, THE EXECUTIONER (1968) Review: Tai Kato’s Unrelenting Profile Of A Murderer

I, The Executioner comes to VOD, Digital, and Film Movement Plus on January 31.

TW: This movie review discusses sexual assault and battery.

This is all in my head at the moment, but I’m really curious as to the influence of classic Japanese films on a certain Korean filmmaker favorite of mine whose latest completed film I’m yet to capture. For now though, I’m happy to continue my own growth in that direction as I get to examine a little bit of the post-war cinematic work of Tai Kato these days. This time, it’s I, The Executioner, also known as Requiem For A Massacre depending on the marketing.

Chalk this one up as another masterpiece by one of the most revered filmmakers of his time – and ours – gathering a cast of characters who are as complex as they are compelling in their deconstruction. That’s really what pulls you in as the story unfolds with a series of rapes and murders that begins following the suicidal death of a young teenager, and attempts by the police and inspectors to try and get at the root of the crime before the killer lands his next target.

That effort is all but futile as I, The Executioner unravels its even more beguiling look at its core character in the foreground, Kawashima (Makoto Sato), a man on a vicious crime spree targeting women who are firstly seen at the top of the film playing a game of Mahjong; The first victim is a woman seen taken captive, raped and forced to write out a hit-list of her cohorts before being unalived herself, stabbed so hard that the killer cuts himself on his own blade before picking the knife back up and finishing what he started.

The death of the first woman is enough to shake the women up at first, but neither of them really know what the killer’s motivations are until they are each confronted, and by the time they realize what’s happened, it’s already too late. As chaos unfolds in the backdrop of his actions, Kawashima’s attention also turns to Haruko (Chieko Baisho), a server at her father’s small restaurant. It’s not too long until the two begin nuturing a friendship that grows into something a little deeper – which later compels Haruko’s father to reveal a dark secret she carries to this day, in hopes that he will marry her if their relationship continues to flourish.

Putting it in simpler terms when it comes to Kawashima and his actions, he’s a killer, and knows that he will be punished when the time comes; We later discover that he has a few more skeletons in his closet which further threatens to upend any potential future for him and Haruko. What’s just as engrossing about Kawashima after this are his motivations for going after the women allegedly at the center of the crime in the film.

I, The Executioner works with very little in this aspect, and applies as much as it can in fleshing out its story, adding layers to Kawashima and Haruko to craft a hearty, visually poetic profile of two complicated people, albeit centering Kawashima as the single-most cross-bearer of the pair. It takes nearly the duration of the film to reveal the absolute crux of the plot, which eventually underscores Kawashima as a maniac on a mission to dispense his own brand of justice. It’s the kind of duality that rightly stirs up chatter at the watercooler among creatives and cinephiles about how to build anything heroic from a character who, in large part, is a shithead. For this, putting a man like Kato next to auteurs like Sidney Lumet, Abel Ferrara, and Martin Scorsese is nowhere near a stretch.

I, The Executioner burns real pretty when it comes to peeling back its layers. It helps that the energy, pacing, and aesthetics keep you pulled in as much as the acting, discernible cinematography, mild gratuity, and Hajime Kaburagi’s hypnotic vocal score do. Kato does a fantastic job at having you pick you pick his brain between each development and plot point as we follow this dark romantic tale of justice mired in murder, sexual violence, and retribution. It’s the kind of story that definitely couldn’t be told the way Kato tells it here, making this film wholly worth experiencing at least once if you’re a collector.

Native New Yorker. Been writing for a long time now, and I enjoy what I do. Be nice to me!