Remembering YEN CHENG-KUO: From Child Star to Redeemed Director, a Life Cut Short at 50

The Taiwanese film world is in mourning following the sudden passing of Yen Cheng-Kuo (顏正國), the beloved child actor who captivated audiences as the plucky “A-Kuo” in the 1980s Kung-Fu Kids (好小子) series. Yen died on October 7, 2025, at 4:57 p.m. at Far Eastern Memorial Hospital in New Taipei City’s Banqiao District, succumbing to stage 4 lung adenocarcinoma after being removed from life support. He was just 50 years old, three days shy of his 51st birthday on October 10. Funeral director and social media influencer Juan Chiao-pen (阮橋本), known as “Steel Dad,” announced the news on Facebook, conveying the family’s profound grief while requesting privacy during this difficult time.

Yen Cheng-kuo’s passing has sparked an outpouring of tributes from fans, filmmakers, and industry veterans who witnessed his evolution from a wide-eyed child star to a resilient artist. Director Hou Hsiao-hsien (侯孝賢), who mentored Yen in his early years, and peers from the Kung-Fu Kids era have shared fond memories of his indomitable spirit. Perhaps the most poignant tribute comes from prolific Taiwanese director Chu Yen-ping (朱延平), known for helming Kung-Fu Kids and a string of bold, genre-defining films. In a heartfelt Facebook post, Chu reflected on Yen’s journey: “In my memory, A-Kuo was smart, stubborn, and fiercely competitive.” This sentiment encapsulates a life defined by meteoric highs, crushing lows, and an inspiring redemption that continues to resonate with audiences and the industry alike.

Born on October 10, 1974, in Keelung, Taiwan, to a family of modest means—his father a retired special forces soldier and his mother a homemaker raising four children—Yen entered the spotlight at age 4 through a children’s acting workshop. By 6, he made his film debut in Li Hsing’s (李行) The Time to Live and the Time to Die (原鄉人), a poignant drama that set the tone for his early roles in Taiwan New Cinema classics.

Under the guidance of auteur Hou Hsiao-hsien, Yen became a fixture in the 1980s Taiwanese film renaissance. He starred in landmark films like Cute Girl (就是溜溜的她, 1980)—Hou’s directorial debut—Cheerful Wind (風兒踢踏踩, 1981), The Boys from Fengkuei (風櫃來的人, 1983), and Growing Up (兒子的大玩偶, 1983), earning a Golden Horse Award nomination for Best Leading Actor in the latter at just 9 years old. These roles showcased his natural talent for portraying the innocence and grit of rural Taiwanese youth, collaborating with icons like Chang Hsiao-yen (張小燕) and Phoenix Fei (鳳飛飛).

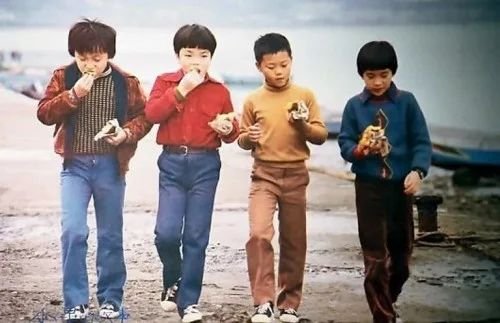

Yen’s breakthrough came at age 12 with the 1986 action-comedy Kung-Fu Kids (好小子), directed by Chu Yen-Ping ( 朱延平) and Chang Mei Chun (張美君), As the street-smart A-Kuo, Yen headlined a trio of pint-sized martial artists alongside Tso Hsiao-hu (左孝虎) and Chen Chung-jung (陳崇榮), blending slapstick humor with rudimentary fight choreography. The film’s massive success spawned five sequels through 1990, including Kung-Fu Kids II and Kung-Fu Kids: The Little Dragons, turning Yen into a household name and Taiwan’s answer to the Goonies with a kung fu twist. His younger brother, Yen Cheng-chieh (顏正傑), and uncle, actor Jen Chang-pin (任長彬), also entered the industry, making the Yens a mini-dynasty of child stars.

Behind the scenes, Yen’s ascent was fueled by raw determination. As his mentor, Chu Yen-Ping recalled, before filming Kung-Fu Kids, co-star Tso—trained at the Fuxing Drama School—excelled in flips and weapons. Yen, a martial arts novice, trained rigorously for a month under a stunt coordinator. His stubborn pride shone through: “He learned backflips, trampoline jumps, and nunchaku skills—all the movie’s stunts. On screen, you couldn’t tell he’d only practiced for a month.” Fame followed swiftly, but so did its shadows.

Adolescence brought unforeseen torment. The Kung-Fu Kids hype made Yen a target for schoolyard bullies. Older students mocked him: “You’re the tough kid from the movie—fight us!” Physically smaller and academically behind due to his acting schedule—he’d repeated first grade and dropped out multiple times—Yen sought refuge in gangs for protection. This led to addiction and crime: arrests for amphetamines in 1991, firearms possession after A Brighter Summer Day (少年吔,安啦!, 1992)—where he delivered a raw performance as a delinquent, ironically earning a disqualified Golden Horse nomination—and thefts between 1996 and 1998.

The nadir came in 2001. Yen and accomplices kidnapped a drug dealer in Changhua County, demanding NT$2 million and 2 kg of amphetamines. Though he denied direct involvement, Yen surrendered and faced the death penalty under Taiwan’s then-active Anti-Banditry Law (懲治盜匪條例). The law’s repeal in 2002 spared him; he was sentenced to 15 years, serving 11 at Taichung Prison before parole in March 2012 for good behavior. A pivotal moment: attending his father’s funeral in shackles awakened his resolve to change. “That was when I realized what it truly means to fight for family,” he later reflected.

Out of prison, Yen channeled his tenacity into reinvention. He studied calligraphy under master Chou Liang-tun (周良敦), developing the “Yen Five Methods” (顏氏五法) and teaching classes as therapy and income. He embraced philanthropy, advocating against drugs and mentoring ex-convicts. In 2015, he returned to acting in Parking (車拼) and Gatao (角頭), roles that drew on his lived experience without exploiting it.

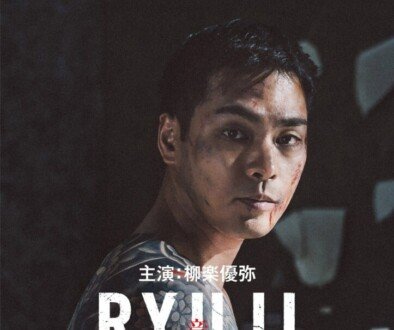

His directorial debut, Gatao 2: Rise of the King (角頭2:王者再起, 2018), was a triumph. In just two to three years of self-taught filmmaking—mirroring his rapid martial arts mastery as a kid—Yen helmed this gangster epic, grossing NT$127 million and earning three Golden Horse nominations. Hou Hsiao-hsien attended the premiere in support, a full-circle moment for the mentor who once pulled a young Yen from the streets. Yen followed with the self-directed A Boy Called Po (少年吔, 2022), a semi-autobiographical tale of juvenile delinquency starring real ex-offenders, paying homage to his A Brighter Summer Day roots.

In 2020, Yen published his autobiography, Letting Go of My Fists, Painting a New Life: The Awakening of Yen Cheng-Kuo (放下拳頭,揮毫人生新顏色:好小子顏正國的青春與覺醒), chronicling his path from “fists” to forgiveness. As his mentor Chu Yen-Ping noted on his facebook post, “From watching him lost and then finding his way back, it filled me with relief. Hearing this news, I’m heartbroken—I’ve lost a junior ready to shine, and the film world has lost a great talent.”

Yen’s final Facebook post, on September 17, 2025, showed him traveling in Tianjin, China, wishing followers health and joy—unaware his battle with lung cancer was nearing its end. His wife, Liu Yu-chen (劉又甄), later shared on his page: “He faced the illness fearlessly, saying he’d completed his mission.”

From the boy who flipped into stardom to the man who scripted his own comeback, Yen Cheng-Kuo embodied Taiwan’s cinematic spirit: raw, unflinching, and ultimately redemptive. As fans flood his social media with memories of Kung-Fu Kids antics and tributes to his later wisdom, one thing is clear—his story, like his films, will endure, reminding us that even after the darkest falls, it’s possible to rise again.

Rest in peace, A-Kuo.

Lead image credit: Xu Fangzheng (source)

Living through Cinematic memories while surviving the most putrified film swamps