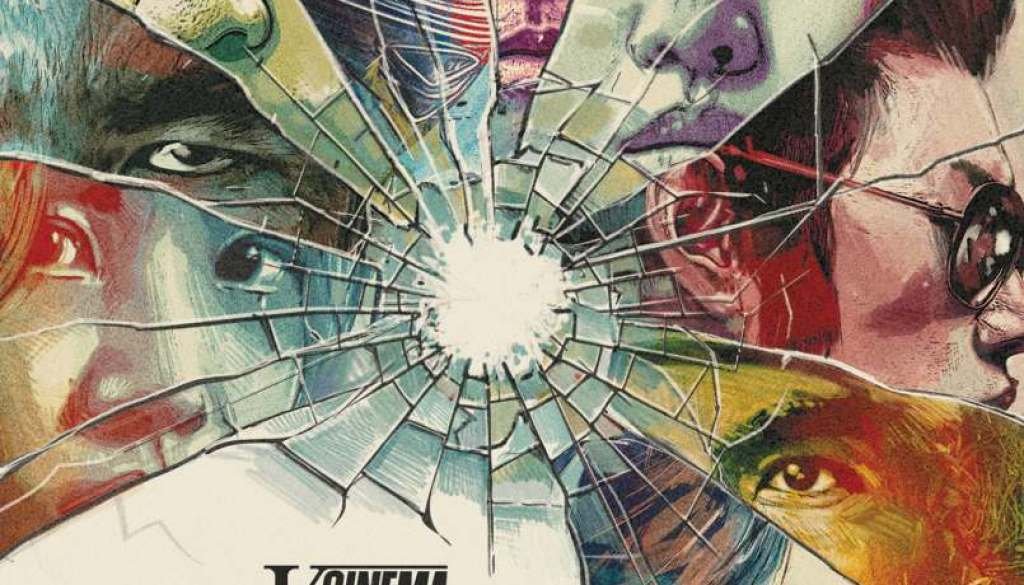

Arrow Video’s V-Cinema Essentials: Bullets & Betrayal Review – Part Two: STRANGER, and CARLOS

Anchors:

• STRANGER

• CARLOS

• CONCLUSION

Remember this movie? I do, which makes it delightful to find out that this next V-Cinema classic comes from the same director…

I’m talking Shunichi Nagasaki who, upon planning his 1991 thriller, Stranger, eventually stepped up to write the script himself when the studio couldn’t find a writer. He did find his lead actress though, with Yuko Natori stepping up for the lead role with the support of co-stars Kentaro Shimizu, and Takashi Naito.

A secretive phone call opens up our tale of sordid betrayal and harrowing redemption lived down in the eyes of Kiriko (Natori), a former bank teller betrayed by her lover, Kenichi (Naito), and arrested for bank fraud. A few years of prison later, the ex-convict can be seen toiling away behind the wheel of a taxi, earning a living for herself while working to pay off her mandated fines for which she’s still in arrears.

For what it’s worth though, Kiriko is still afflicted by a brokenheart, and for largely that reason, she still keeps to herself. Hell, the only company she’ll ever tolerate is the neighbor’s barking dog, and her fish. Her boss insists she works the dayshift to bring in more fares, despite her preference toward working at night. Adding to her daily ire, she is treated like an oddity in her male-dominated work environment by some, while others peskily seek her attention and adoration, including co-worker, Kijima (Shimizu).

Of course, her preferred evening hours are no real picnic either; It’s not all bad, although she could do way better without the occasional horny couple, nauseous drunk, or presumptuous preachy passenger touting religion. To be fair though, the latter certainly speaks more to the narrative of Stranger, and the stoic nature our protagonist takes on given how eerily close her past feels, not to mention the symbolic nature of this sensation that now manifests in the form of a mysterious black truck whose driver has begun stalking and terrorizing her.

That’s the brilliance of Nagasaki’s Stranger, which reads like an essay on forgiveness in multiple dimensions. Part of Kiriko can’t forgive herself for falling so hard only to get hurt once for her involvement in a criminal scheme. Her reluctance to deal with anyone trying to get close to her is as clear and present as the danger in her wake, namely as Kijima tries so hard to win her over. He’s not necessarily a bad person, but his methods aren’t exactly apropos which, understandably, validates Kiriko’s instinct to dismiss him at nearly every turn.

As the movie has it, however, it is Kijima’s stubborness-enveloped concern that bodes as crucial to Kiriko’s survival. There’s a minor plot device earlier on involving this character that drives this as well, which also makes you wonder just what the hell this character was thinking when doing what he did prior to later events. It’s bizzare, but to the film’s credit, purposeful.

Much of this is par for the course in the subplotting for Kiriko’s evolution and progression as she learns to lower her guard just a little. Alas, you better believe her defenses are right back up when her stalker strikes. His face is hardly visible when we first meet him, that is, compared to the discernible scar on his right wrist which she spots almost instantly when she first drives him.

Kiriko only comes to realize that this is the same mysterious person tailing her in his rugged, mud-stained black truck, watching her from a distance in the day, and then pouncing on her at night. To her credit, her reflexes are fast. The first major attack doesn’t happen until well into the first half of the film, and the calls are so close thereafter, it’s almost nervewracking, and it’s all pretty much downhill from there. Whether it’s with a hammer, an axe, some traumatic foreshadowing and gruesome stochastic imagery, or just his own truck, this psychopath is doing whatever it takes to torment Kiriko, essentially playing with his pray.

Making matters worse is that not even Kiriko knows if these attacks are connected to her past crimes, although it doesn’t really matter at this juncture. The paranoia has set in, and it’s all on Kiriko to burn past her breaking point with enough resolve to take her would-be killer down once and for all.

What ensues is an imminent game of cat-and-mouse the likes of which would arouse any genre fan. Nagasaki’s own admitted inspiration from Steven Spielberg’s road terror classic, Duel, speaks to his applications here, from set pieces to cinematography and tone, showcasing Natori in fine form as a fierce underdog worthy of her mettle, and the respect of her working class peers.

To that end, in my view, Stranger delivers taut, cinematic prose on what it means to remind yourself that as hard as life gets, you’re never really alone. Ideal? Perhaps. Trite? I guess, but that all depends on the viewer. A movie can only reflect certain aspects and metrics about life and living that are intended for its audience. Given how tough times certainly are these days, it’s reasonable to believe no one will hound you for not wanting to feel like a stranger in your own skin when you wake up.

Idunno. That’s just me. Maybe I’m overthinking it, which is more than I can say for Nagasaki per his interview on the disc. He just wanted to direct a thriller about a female cab driver and put together the right script to do it. To add, it reunited him with Natori three years after a film they did together, and according to his interview featured on the disc, with the launch of V-Cinema right then, the opportunity couldn’t have come at a better time.

Going into the disc’s second presentation, the same goes for Carlos, the 1991 adaptation of the manga of the same name by its author, Kazuhiro Kiuchi of Be-Bop High School franchise fame; Kiuchi, per his interview on the disc, even goes into how he and the well-known cinematographer he “miraculously” brought on board the project, Seizo Sengen, worked together to mix and mingle their own ideas to help culminate Kiuchi’s vision.

Prime in that manifestation was Kiuchi’s casting of actor Naoto Takenaka for the part, in capturing his tale of the crime-ridden disapora of non-Japanese people in his explosive thriller. Specifically, Kiuchi spotlights a gang of Brazilian-Japanese gangsters led by Carlos (Takenaka), a Brazilian exile living in Japan and making a name for himself as a gun runner out of his bar. Indeed though, as essential as his business is to the locals, the first major scene in which we meet our titular anti-hero makes it clear that outsiders like him and his ilk are less than welcome. Alas, for Carlos, what better way to react to dispositions like this than do what criminals pissed in the moment usually do?

As Kiuchi’s story and vision have it, there’s a certain entertainment value when it comes to foreigners, and if you’re a brazen Japanese gangster with no sense of conscious thought on the world outside your bubble, you’re probably one of the first two poor schmucks who gets their brains blown away by Carlos near the top of the film after trying to rip him off. The good news there, at least for now, is that nobody suspects him. Not the two rival yakuza gangs at war with each other, not their enforcers or the corrupt officials acting in their favor, and certainly not the dirty cop who pays Carlos a visit asking for information on who did them in.

Little does Carlos know that the two men he killed worked for Yamashiro, (Minoru Oki), the ailing boss of the Yamashiro clan who loses his shit when he learns his underlings called a surprise meeting one morning about who to succeed as the new boss. Rather, Yamashiro is intent on holding his seat with the goal to handing it to the first of his soldiers who manages to kill his rival, Hayakawa (Yuzo Hayakawa), regardless of any proof to the matter.

With the power vacuum in place, a dirty police lieutenant and Yamashiro loyalist named Katayama (Ryuji Katagiri), eager to take the seat, hires Carlos to kill Hayakawa. Before Carlos can move, however, Katayama’s competition, Sato (Goichi Yamada) manages to bring in some outside help of his own in the form of a burly caucasian professional killer (Chuck Wilson) who manages to get the job done swiftly.

That kind of timing doesn’t exactly bode well for Katayama who implores Carlos to act fast and get rid of his competition, adding a discernible body count to a backdrop of violence in a scheme that spurs out of control. When that happens, it’s only a matter of time – and bullets – before Carlos, his crew, and his family are put in danger.

That’s where the film’s moored charm comes into play, bringing full circle a protagonist who, from the first moments of the movie, is more than meets the eye. He’s his own boss, someone with little to lose, and it’s right when we reach that particular point in the film that we see just how bad it gets when you’re on Carlos’s shitlist. There’s even a scene toward the end of the film that speaks ardently to fans of every action film whose dangerous past is suddenly brought back into relevance with a single news bulletin.

It’s safe to say that Takenaka was a perfect choice for this role at the time, any way you slice it. He’s become a versatile actor over the years (fun fact: Takenaka gets a brief on-screen reunion with fellow V-Cinema greats like Kane Kosugi, Show Aikawa, and Masaya Kato in Ten Shimoyama’s Blood Heat, which you can read more about here) although surprisingly, Carlos, much like the the manga on which this film is based, is largely omitted from the actor’s works (I’ve seen four films in this V-Cinema collection up to now and this is just one of two that were missing from a few movie websites, which is weird). Looking at Takenaka, you might not have guessed him for the role of a film like this depending on your tastes, but Kiuchi’s decision was wise as hell here, mainly with the role being written with Takenaka in mind.

Guns are also core to the film’s story, being an action crime thriller with its fair share of gun play and violence. Editing was one area that director Kiuchi was keen on minding as he shot the gun battles – something he also talks about during his interview. Firearms are also part of Jonathan Clements’s focus during his seperate video essay on the disc when discussing Carlos, chiming in on how guns played a role in director Kiuchi’s upbringing. They’re the weapons of choice for much of the way in Carlos, which, to Kiuchi’s credit, gave further proof to the film’s real storytelling muscle surrounding our main character’s evolution. He’s a killer, or sure, and even a scumbag, but he is a survivor, quick on his feet and clearly able to handle himself at almost any turn. To this, Kiuchi more than welcomes to suspend disbelief in watching a movie rife with bad guys, as he endulges you with reasons aplenty in Takenaka’s portrayal of a bad guy worth cheering.

Watching Carlos and taking in the extras – minus a trailer, and including another introduction by film critic Masaki Tanioka for both titles, Arrow Video further cements V-Cinema as an investment worth making for today’s film fandom and home media enthusiasts. Agreeably though, not all of these films sit with everyone. I’ve enjoyed what the Arrow Video boxset has offered so far as each of these titles were curated by scholars who’ve done their research and are knowledgeable on what titles would be worth reintroducing to a new crop of film fans today. As many good titles as there were, there are probably just as many bad ones, at that, which, according to Kiuchi, is something that working as a V-Cinema director was afforded as a caveat with the creative freedoms these filmmakers were given.

If you enjoyed this article, please consider donating to my Buy Me A Coffee page and supporting my work to keep me going.

Native New Yorker. Been writing for a long time now, and I enjoy what I do. Be nice to me!