Asian World 2025 Review: In DEAD TO RIGHTS, A Harrowing Snapshot Of Endurance

I’ve yet to discover more of Shen Ao’s work beyond what I’ve read and scanned in the trades in the past decade. He’s no stranger to patriotic narratives though – something he revisits in his latest World War II drama, Dead To Rights, which follows a postal worker cornered by the imperial Japanese and mistaken for a photo developer, and forced to learn the trade in order to help keep himself, as well as an innocent family alive.

Underscoring the synopsis here is the film’s setting in Nanjing, the site of some of the empire’s most horrific and gruesome crimes committed during the war. I forget what year exactly it was when I learned about this in school, except all I remembered was how I felt about not learning about this incident years earlier. It felt like a whole gap had just been filled, while leaving me wondering just how many more there were in its wake. I’m in my forties now, and I look back on my educational upbringing with a huge side-eye at times.

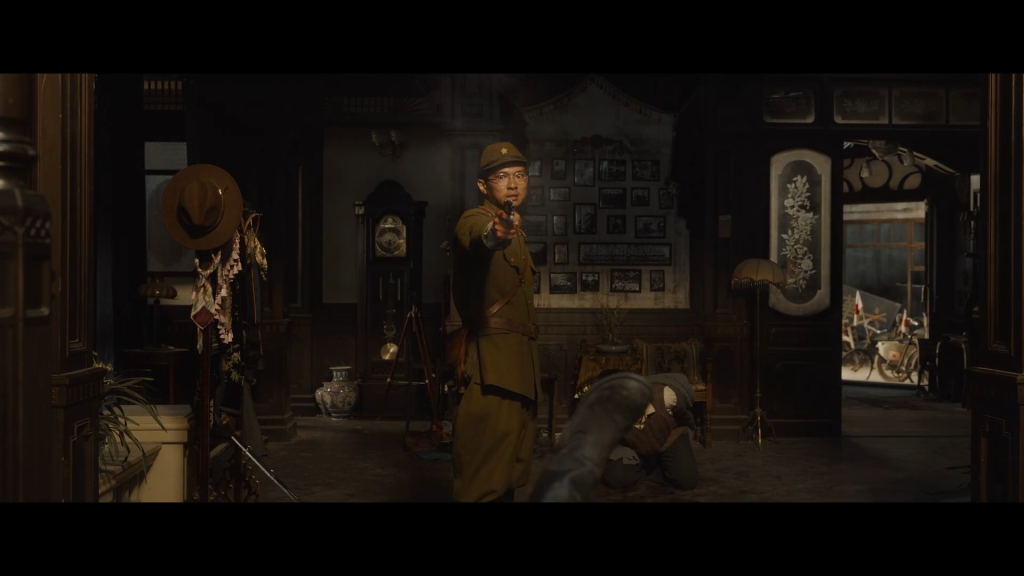

Like other World War II films that profile the Axis Of Evil in all its history, Dead To Rights is no different. Shen’s film bares all the trimmings of an unnerving top-to-bottom survival tale, with Liuchang (Liu Haoran) reluctantly thrust into a whole different occupation when an ambitious Japanese war photographer named Hideo (Daichi Harashima) mistakes him for a photo developer.

It is here that Liuchang is cornered by Hideo into developing a batch of photos to help impress the generals, and he’s on the clock. Fortunately, the studio he winds up at has an operator named Chengzong (Wang Xiao) who specializes in photo development, and whose family is hidden in the cellar as refuge from the Japanese. Nonetheless, it’ll be up to Liuchang to learn the ropes in order to develop the photos properly while playing his part as its sole operator with Chengzong and his family in hiding.

In addition to Chengzong’s wife, Yifan (Wang Zhen Er) and daughter, Wanyi (Yang Enyou), we also meet Guanghai (Wang Chuanjun), a translator desperately towing the line between obedience and bitterment with Japanese forces as he works to mitigate communcations with the locals, as well as Yuxiu (Gao Ye), a lounge singer and former actress who still pines for her glory days in front of the lens. The cast of mains round out with Cunyi (Zhou You), a wounded soldier Yu Xiu secretly brings into the cellar as the Japanese have already begun targeting and executing any Chinese person who resumes any traits indicative of military service.

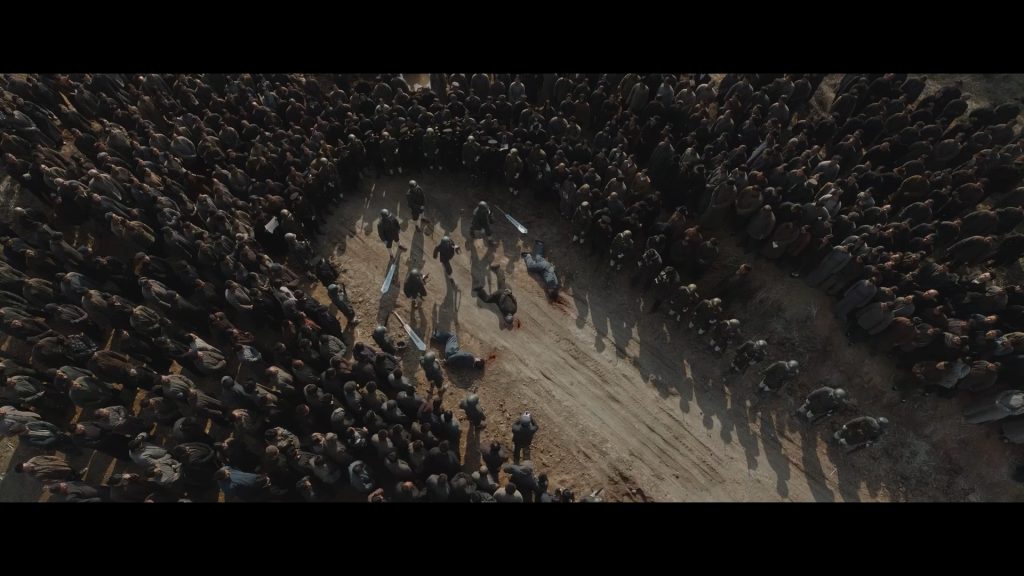

That last bit is just one in the many areas of war crimes that are central to the film’s crux which revolves around Japan’s warcrimes as committed per the laws of the Geneva Convention. Shen’s story firmly elucidates these crimes in many scenes, with some of the most discernible, and rather indescrible ones. They’re shot with tact and many of them suggestive tone to contribute to their necessary impact so as to not come off as exploitative. Even so, there are a few that may leave a pit in your stomach, including a scene in which Liuchang and Yixiu are coerced by the Japanese into taking a picture together with a baby to look more like a family. As far as descriptions go, I’ll leave it there.

Liu and Harashima’s enmity with one another is another key spotlight to the story. It’s a little unnerving to watch Liuchang at times because you get the idea that he doesn’t really know how to play things by ear; There’s a scene where Hideo starts feigning friendship and erroneously calling Liuchang “A-tai,” and even though Liuchang tries to correct him, Guanghai has to filter everything accordingly. Provided you remember Gordon Lam’s character from 2008’s Ip Man, you get the idea, and what’s even more delightful is what happens toward the film’s climax when things between Liuchang and Hideo reach a fiery peak.

Actresses Wang and Gao also have their phases with each other. Wang’s part is somewhat minimal but still carries its essential weight to the story, as a mother struggling to maintain her own identity and womanhood. It’s awkward, initially, as Yifan doesn’t take too easily to Yixiu at first, but they grow a little closer by the end as the group relies a little more on each other. Young actress Yang is the requisite spark of the group whose innocence helps anchor the film’s optimistic allure.

Interestingly, Dead To Rights places plenty of its focus on this group’s survival and emotional tumult throughout throughout story. It’s a substantive placeholder leading up to the film’s residual fallout and explosive finale, particularly as Japan forces are inclined to help maintain morale by letting soldiers do their dishonorable worst while keeping as low a profile from the world’s eye. It’s well within the film’s last half hour that we learn about the group’s scheme to help leak some of Japan’s photos to cities outside Nanjing, thus ensuing the war crimes tribunal years later which held Japanese military forces accountable for its warcrimes.

Dead To Rights has a lot of moving pieces throughout its two-and-a-quarter hour runtime, during which Shen manages to deliver an engrossing tale of triumph amid tragedy. I’ll tell you right now – only one key character comes alive out by the film’s recapitulation. The rest is a tale recorded in history, amplified by artists like Shen and performed aptly by a cast that makes Dead To Rights an affirmative snapshot in historical narrative war cinema.

Dead To Rights is China’s official entry into the 98th Academy Awards. The film previously released in select theaters back in August from Niu Vision Media, and has screened this week as part of the 11th Asian World Film Festival which runs through November 20. From China Film Group, Beijing Super Lion Culture Group, and Yuye Media.

Native New Yorker. Been writing for a long time now, and I enjoy what I do. Be nice to me!