Fantasia XXVIII Review: In Junichi Yasuda’s A SAMURAI IN TIME, A Hearty Slice-Of-Life Romp That Cuts Deep

4.5 min. read

To say the Covid-19 pandemic was a challenging factor to film and TV production was an understatement. Still, with a little gumption and good faith investment, filmmakers like Junichi Yasuda could make themselves and film fans whole, which is exactly the case for his latest fish-out-of-water fantasy dramedy, A Samurai In Time, which screens for the 28th edition of the Fantasia International Film Festival.

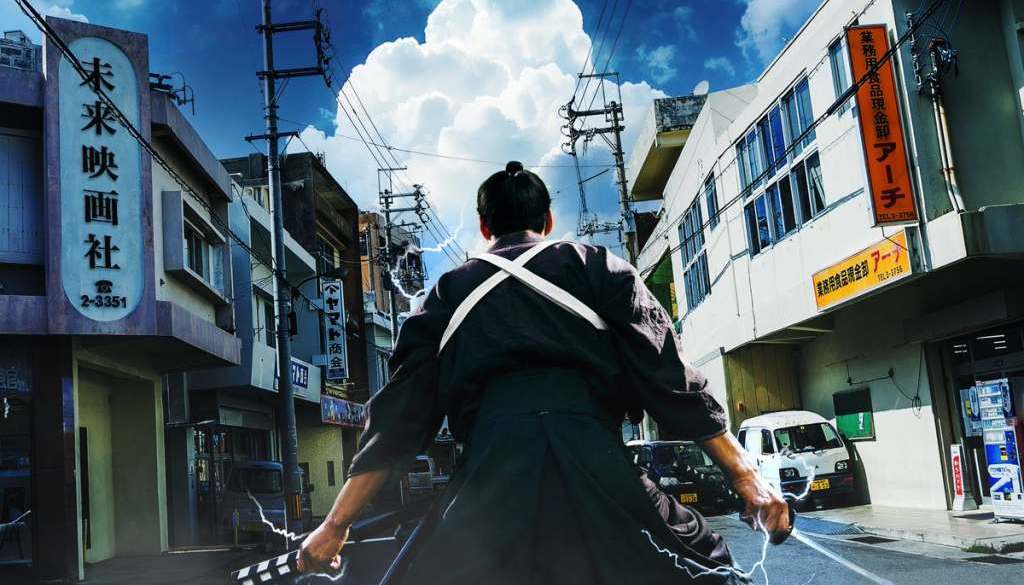

Directed from a script also written by Yasuda, the first five minutes are set in late 19th century Edo, with Shogunate loyalist Shinzaemon Kasara (Makiya Yamaguchi) on the cusp of dueling a legendary young, anti-Shogunate samurai moments before being struck by lightning. Dazed and daunted by morning, Kasara awakens only to realize that not only he isn’t where he’s supposed to be, but also, when.

Between getting excoriated and stared at by a jidaigeki cast and crew who think he’s a wayward background actor who may or may not be amnesiac, Kasara eventually manages to find direction from a helpful handful. Assistant director Yuko (Yuno Sakura) is the first to come to his aid after spotting the vagrant and displaced samurai post-head injury, followed by the caretakers of the Seikeiji temple around the corner from the production lot (Beni Manko and Yoshiharu Fukuda) who take Kasara in as one of their own.

Yasuda’s A Samurai In Time spends the remainder of its two hour-plus duration crafting an epic, dramatic, slice-of-life tale of self-reflection and exploration for our protagonist, as he copes with life in a modern day setting. The time travel aspect of the story is largely ornamental to its progression, and treated as an afterthought as the film moves forward. The mystery of it never gets fully realized among our characters or solved for that matter, although it doesn’t hinder the film much in anyway as the film focuses prominently on Kasara’s growth and evolution.

Even Kasara himself doesn’t fully understand how a bolt of lightning chucked him a century and a half into the future. Still, he completely acknowledges the impasse before him, and through his discovery of the moving picture and the world of film production, places his trajectory squarely under the stewardship of stunt coordinator Sekimoto (Rantaro Mine) in hopes of training to be a kirareyaku, even as the jidaigeki market is on its last legs.

Kasara’s transition also turns physical as he instead grows his hair out from the baldspot he would fashion beneath his traditional top knot, and he even starts wearing modern clothing. Additionally, his reaction to what comes across as an expensive delicacy now enjoyed by common households is as much of a delight to see as his response is to television.

There are some traditions he still adheres to for a time, including his abstinence from alcohol, as well as his celibacy. The latter certainly becomes topical when oftentimes Kasara is confronted over his unrequited feelings for Yuko, a fact often playfully pointed out by a famous jidaigeki star named Kyoichiro Kazami (Norimasa Fuke) who one day comes out of a ten year hiatus to make one final, great samurai epic, hiring Kasara for a key role.

Par for the course with A Samurai In Time is Kasara’s cognizance of history pertinent to his work. A last minute script change Kasara reads is the catalystic fulcrum that puts at stake nearly all the progress he achieved up until now as a screen actor, amplifying the culture shock that later compels him to do what most of the crew deem as the unthinkable: A version of the final fight on Kazami’s film using real swords. The change is the biggest in a series of moments in the film between Kasara and Kazami, as the synergy they share transitions into a quaking intensity between two committed warriors fighting for what they believe in, with a finale that puts a poignant and humanistic touch on Yasuda’s narrative.

That last point deserves reiteration, specifically in the aftermath of the climatic sword finale between two of our main characters amid the dramatic twists and turns along the way, with the scripted fight scene turning into something not-so-scripted after all, and raising the stakes even further. The scene is intense and adrenaline pumping from start to finish, with Yasuda and sword coordinator Kazuto Seike committed to as much energy and potency as possible from start to finish.

There was a point earlier on when A Samurai In Time nearly didn’t happen. Yasuda wore multiple hats on this film, and was joined by a small crew for the beleagured production. If it wasn’t for Toei jumping in to provide this film the support it needed, we wouldn’t have it when we did, and neither would this year’s Fantasia audiences for that matter. It’s a fascinating story full of wonderment, empathy and heart, and it arrives aptly at a time where humanity could use a few more doses of these.

A Samurai In Time was reviewed for the 28th Fantasia International Film Festival which runs from July 18 through August 4.

Native New Yorker. Been writing for a long time now, and I enjoy what I do. Be nice to me!