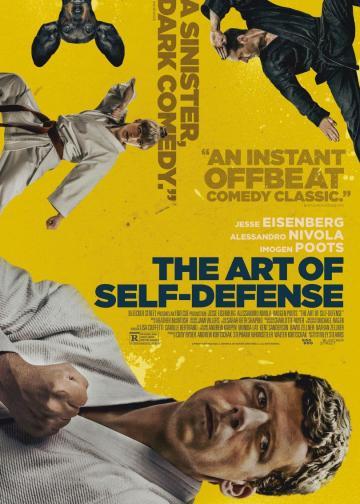

Review: In Riley Stearns’ THE ART OF SELF-DEFENSE, Life Imitates Art Through Violent Catharsis

While not purely outstanding, Nima Nourizadeh’s entertaining out-of-the-blue Jesse Eisenberg action romp, American Ultra, was a definitive change of pace for the actor best known for quieter, more subtle roles emulating innocuous “beta male” types. Such is what you’ll find at the top of Faults helmer Riley Stearns’ The Art Of Self-Defense before the rest of the narrative unfolds from its cautionary exploration of male toxicity with a touch of nudity and gender disparity.

In Stearns’ The Art Of Self-Defense, Casey Davies (Eisenberg) is often fragile – best remembered as that guy everyone likes to belittle at the office while in the way of no one despite his best, albeit mediocre attemps to socialize. He’s an accountant, lives alone with a Dachshund, and is learning French as a means of fulfilling his own minimal wanderlust.

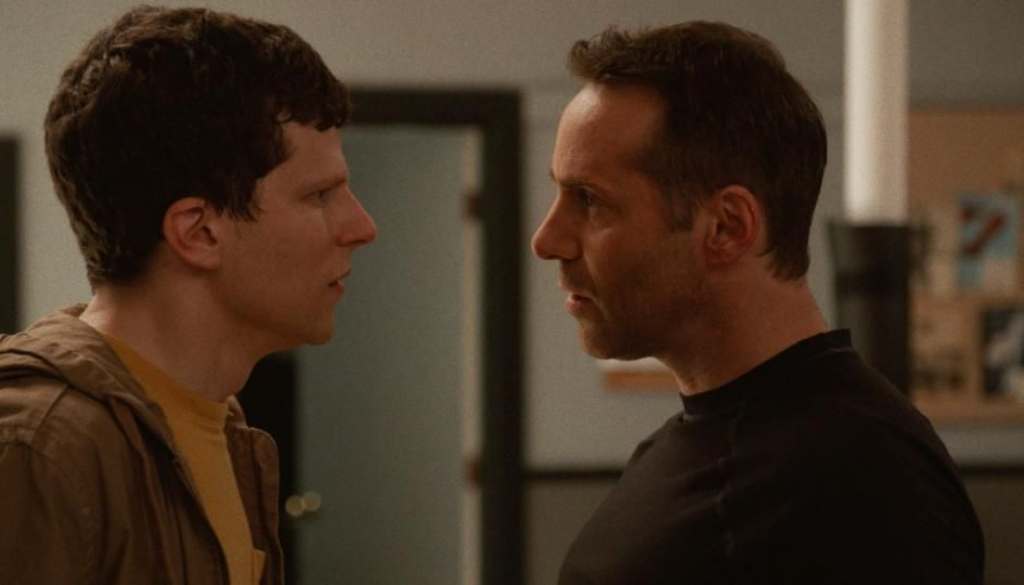

One evening he leaves out to restock on dog food only to find himself the victim of a heinous and senseless mugging by three people in black wearing helmets. After being hospitalized, most of his time is spent at home in fear of his life with next to no interest or reason to go out at night. After humoring himself at a gun shop, he spots a local dojo and enters with the intention of joining, and soon enough, a meeting with the school’s Sensei (Face-Off co-star Alessandro Nivola) all but seals the deal.

From the free introductory class to full matriculation, Casey’s journey is a transformative and enthralling one as he traverses the world of Karate in hopes of learning how to “punch with your feet” and “kick with your fists”. His education under Sensei’s stewardship invokes a visibly strong and ubiquitous commitment to classtime, eventually earning him a rank from white to a confidence-boosting yellow belt. Despite this, Casey knows it’s going to take a little more than his current standard progression, especially if he wants “to be what intimidates” him.

Going forward, Sensei enrolls Casey in a series of intense night classes, effectively to help him earn his “stripes”. Casey reluctantly accepts and much to his chagrin, his first night class turns out to be one of the most brutal – the start of a reveal of a much darker side to the school and its Sensei. By this point, Anna (Imogen Poots), a brown belt in whom Casey manages to accrue as the closest thing to a friend at the school, begins warning him about continuing. This hasn’t stopped the worst from happening, however – lines are crossed, blood has spilled, and Casey must decide if he can “become the Alpha” he needs to be.

It’s easy to forget sometimes that Stearns’ The Art Of Self-Defense is billed as a black comedy considering how evocative the film gets. Nivola’s Sensei role especially contributes to this in scenes opposite our protagonist, and with a character that bodes just as menacing as he feels; the moment he demonstrates how Karate is “a form of communication” exhibits one of the film’s more inordinate moments of humor before treading into darker territory.

Poots’ Anna often falls victim to that ideology, being the only female student in the school, while Sensei’s affront to her for being a woman – and therefore weaker – is more underhanded than direct. You get the idea that Karate is what she’s good at and she’s willing to pay her dues and fight for what she believes is rightfully hers. You also get the notion that she’s crossed a line at one point to do exactly that, and then some. She’s afflicted, but resilient in nature. Her moral compass is questionable to a degree, but she never really loses sight of where North is.

There’s no question that Eisenberg can handle a physical role at this juncture, so seeing him in a martial arts role is pretty prospective despite the film’s more contemplative, more arthouse-suited template. The two training montages are filmed in slow-motion with easy-paced camera zoom-ins, and are scored differently to further emulate Casey’s transformation. His newfound identity is made visible throughout the film on a higher volume; his need to express himself verbally gets more enunciative and authoritarian, and his anger is slightly less inhibited over time.

Co-stars Phillip Andre Botello and Steve Terada, both genuine martial artists, add some pepper to the film’s martial arts millieu with their respective talents. The film’s more stronger outing in this aspect comes from headliner Poots in an intense fight scene with Terada midway in the film. Competent cinematography here does excellently for the actress, coupled with direction from stunt performer and coordinator Mindy Kelly making her feature debut as fight choreographer.

Between the deadpan humor, brutal fight scenes and Eisenberg’s anti-climatic final duel opposite Nivola, Stearns’ focus with The Art Of Self-Defense never lets up on its exploration of the male-dominated environment of Karate, and the imminent toxicity that follows with each layer of the school’s seedy underbelly that Casey gets exposed to. Its serves to what ultimately foments Casey’s own displeasure with Sensei by the second half of the film, and with third act finale culminates a twisted, albeit perfect conclusion that makes The Art Of Self-Defense so incontestible on its message.

Native New Yorker. Been writing for a long time now, and I enjoy what I do. Be nice to me!